Alfred Rappaport Shareholder Value Pdf Merge

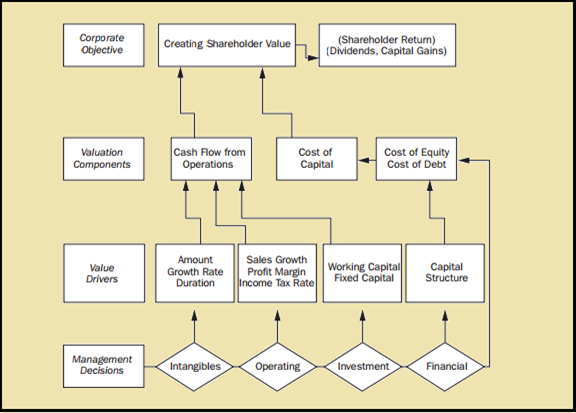

Principles of Shareholder Value Creation. Creating Shareholder Value, Alfred Rappaport provides managers and investors with the practical tools needed to generate superior returns. After a decade of downsizings frequently blamed on shareholder value decision. Creating shareholder value by alfred rappaport PDF rappaport 1986 creating shareholder. Consequently, this buyer would destroy value if it did nothing else but increase the bank's assets at a faster rate. For an excellent discussion, see Alfred Rappaport, 'Converting Merger Benefits to Shareholder Value,' Mergers & Acquisitions (March/April 1987): 49–55. Thomas Hogarty, 'Profits from Mergers: The. In this article, Alfred Rappaport offers 10 basic principles to help executives create lasting shareholder value. For starters, companies should not manage earnings or provide earnings guidance; those that fail to embrace this first principle of shareholder value will almost certainly be unable to follow the rest.

Executive Summary Reprint: R0609C Executives have developed tunnel vision in their pursuit of shareholder value, focusing on short-term performance at the expense of investing in long-term growth. It’s time to broaden that perspective and begin shaping business strategies in light of the competitive landscape, not the shareholder list. In this article, Alfred Rappaport offers ten basic principles to help executives create lasting shareholder value. For starters, companies should not manage earnings or provide earnings guidance; those that fail to embrace this first principle of shareholder value will almost certainly be unable to follow the rest. Additionally, leaders should make strategic decisions and acquisitions and carry assets that maximize expected value, even if near-term earnings are negatively affected as a result. During times when there are no credible value-creating opportunities to invest in the business, companies should avoid using excess cash to make investments that look good on the surface but might end up destroying value, such as ill-advised, overpriced acquisitions.

It would be better to return the cash to shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks. Rappaport also offers guidelines for establishing effective pay incentives at every level of management; emphasizes that senior executives need to lay their wealth on the line just as shareholders do; and urges companies to embrace full disclosure, an antidote to short-term earnings obsession that serves to lessen investor uncertainty, which could reduce the cost of capital and increase the share price. The author notes that a few types of companies—high-tech start-ups, for example, and severely capital-constrained organizations—cannot afford to ignore market pressures for short-term performance. Most companies with a sound, well-executed business model, however, could better realize their potential for creating shareholder value by adopting the ten principles.

Many firms sacrifice sustained growth for short-term financial gain. For example, a whopping 80% of executives would intentionally limit critical R&D spending just to meet quarterly earnings benchmarks. They miss opportunities to create enduring value for their companies and their shareholders. How to cultivate the future growth your firm needs to succeed? Rappaport identifies 10 powerful practices. First among them: Don’t get sucked into the short-term earnings-expectation game—it only tempts you to forgo value-creating investments to report rosy earnings now.

Another practice: Ensure that executives bear the same risks of ownership that shareholders do—by requiring them to own stock in the firm. At eBay, for example, executives have to own company shares equivalent to three times their annual base salary. EBay’s rationale? When executives have significant skin in the game, they tend to make decisions with long-term value in mind. The Idea in Practice Rappaport recommends these additional practices to create long-term growth for your company:. Make strategic decisions that maximize expected future value—even at the expense of lower near-term earnings. In comparing strategic options, ask: Which operating units’ potential to create long-term growth warrants additional capital investments?

Which have limited potential and therefore should be restructured or divested? What mix of investments across operating units should produce the most long-term value?. Carry assets only if they maximize the long-term value of your firm. Focus on activities that contribute most to long-term value, such as research and strategic hiring. Outsource lower value activities such as manufacturing. Consider Dell Computer’s well-chronicled direct-to-consumer custom PC assembly business model. Dell invests extensively in marketing and telephone sales while minimizing its investments in distribution, manufacturing, and inventory-carrying facilities.

Return excess cash to shareholders when there are no value-creating opportunities in which to invest. Disburse excess cash reserves to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks. You’ll give shareholders a chance to earn better returns elsewhere—and prevent management from using the cash to make misguided value-destroying investments.

Reward senior executives for delivering superior long-term returns. Standard stock options diminish long-term motivation, since many executives cash out early. Instead, use. These options reward executives only if shares outperform a stock index of the company’s peers, not simply because the market as a whole is rising. Reward operating-unit executives for adding superior multiyear value.

Instead of linking bonuses to budgets (a practice that induces managers to lowball performance possibilities), develop metrics that capture the shareholder value created by the operating unit. And extend the performance evaluation period to at least a rolling three-year cycle. Reward middle managers and frontline employees for delivering superior performance on key value drivers they influence directly. Focus on three to five leading value-based metrics, such as time to market for new product launches, employee turnover, customer retention, and timely opening of new stores. Provide investors with value-relevant information. Counter short-term earnings obsession and investor uncertainty by improving the form and content of financial reports.

Prepare a corporate performance statement that allows analysts and shareholders to readily understand the key performance indicators that drive your company’s long-term value. It’s become fashionable to blame the pursuit of shareholder value for the ills besetting corporate America: managers and investors obsessed with next quarter’s results, failure to invest in long-term growth, and even the accounting scandals that have grabbed headlines. When executives destroy the value they are supposed to be creating, they almost always claim that stock market pressure made them do it. The reality is that the shareholder value principle has not failed management; rather, it is management that has betrayed the principle. In the 1990s, for example, many companies introduced stock options as a major component of executive compensation. The idea was to align the interests of management with those of shareholders.

How To Increase Shareholder Value

But the generous distribution of options largely failed to motivate value-friendly behavior because their design almost guaranteed that they would produce the opposite result. To start with, relatively short vesting periods, combined with a belief that short-term earnings fuel stock prices, encouraged executives to manage earnings, exercise their options early, and cash out opportunistically. The common practice of accelerating the vesting date for a CEO’s options at retirement added yet another incentive to focus on short-term performance. Of course, these shortcomings were obscured during much of that decade, and corporate governance took a backseat as investors watched stock prices rise at a double-digit clip. The climate changed dramatically in the new millennium, however, as accounting scandals and a steep stock market decline triggered a rash of corporate collapses. The ensuing erosion of public trust prompted a swift regulatory response—most notably, the 2002 passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), which requires companies to institute elaborate internal controls and makes corporate executives directly accountable for the accuracy of financial statements. Nonetheless, despite SOX and other measures, the focus on short-term performance persists.

In their defense, some executives contend that they have no choice but to adopt a short-term orientation, given that the average holding period for stocks in professionally managed funds has dropped from about seven years in the 1960s to less than one year today. Why consider the interests of long-term shareholders when there are none?

This reasoning is deeply flawed. What matters is not investor holding periods but rather the market’s valuation horizon—the number of years of expected cash flows required to justify the stock price. While investors may focus unduly on near-term goals and hold shares for a relatively short time, stock prices reflect the market’s long view. Studies suggest that it takes more than ten years of value-creating cash flows to justify the stock prices of most companies. Management’s responsibility, therefore, is to deliver those flows—that is, to pursue long-term value maximization regardless of the mix of high- and low-turnover shareholders. And no one could reasonably argue that an absence of long-term shareholders gives management the license to maximize short-term performance and risk endangering the company’s future. The competitive landscape, not the shareholder list, should shape business strategies.

The competitive landscape, not the shareholder list, should shape business strategies. What do companies have to do if they are to be serious about creating value? In this article, I draw on my research and several decades of consulting experience to set out ten basic governance principles for value creation that collectively will help any company with a sound, well-executed business model to better realize its potential for creating shareholder value. Though the principles will not surprise readers, applying some of them calls for practices that run deeply counter to prevailing norms. I should point out that no company—with the possible exception of Berkshire Hathaway—gets anywhere near to implementing all these principles. That’s a pity for investors because, as CEO Warren Buffett’s fellow shareholders have found, there’s a lot to be gained from owning shares in what I call a level 10 company—one that applies all ten principles.

(For more on Berkshire Hathaway’s application of the ten principles, please read my colleague Michael Mauboussin’s analysis in the sidebar “Approaching Level 10: The Story of Berkshire Hathaway.”) Approaching Level 10: The Story of Berkshire Hathaway. By Michael J. Mauboussin Do any companies in America make decisions consistent with all ten shareholder value principles? Berkshire Hathaway, controlled by the legendary Warren Buffett, may come the closest. Not only is Buffett the company’s largest shareholder, but he is also in the rare position of viewing the drivers of shareholder value through the eyes of a major investor and executive.

He observes, “I’m a better businessman because I am an investor and a better investor because I am a businessman. If you have the mentality of both, it aids you in each field.” 1 In Berkshire’s communications, for example, Buffett makes it clear that the company does not “follow the usual practice of giving earnings ‘guidance,’” recognizing that “reported earnings may reveal relatively little about our true economic performance” (see Principle 1). Instead, the company vows to be “candid in our reporting to you, emphasizing the pluses and minuses important in appraising business value. Our guideline is to tell you the business facts that we would want to know if our positions were reversed. We owe you no less” (Principle 10). Berkshire’s capital allocation decisions, especially when earnings growth and value creation conflict, are also consonant with the shareholder value principle.

Writes Buffett, “Accounting consequences do not influence our operating or capital-allocation decisions. When acquisition costs are similar, we much prefer to purchase $2 of earnings that are not reportable by us under standard accounting principles than to purchase $1 of earnings that is reportable” (Principles 2 and 3). Shareholder-value companies recognize the importance of generating long-term cash flows and hence avoid actions designed to boost short-term performance at the expense of the long view. Berkshire’s 2005 annual report explains the company’s position: “If a management makes bad decisions in order to hit short-term earnings targets, and consequently gets behind the eight-ball, no amount of subsequent brilliance will overcome the damage that has been inflicted.” Berkshire is also exceptional with regard to its corporate governance and compensation. There’s no doubt that Buffett’s wealth and that of the company’s vice chairman, Charlie Munger, rise and fall with that of the other shareholders: Berkshire stock represents the vast majority of their substantial net worth (Principle 9).

As Buffett notes, “Charlie and I cannot promise you results. But we can guarantee that your financial fortunes will move in lockstep with ours for whatever period of time you elect to be our partner.” The company’s compensation approach is also consistent with the shareholder value principle and stands in stark contrast to common U.S. Compensation practices.

Buffett’s $100,000 annual salary places him in the cellar of Fortune 500 CEO pay, where median compensation exceeds $8 million. Further, Berkshire is the rare company that does not grant any employee stock options or restricted stock. Buffett is not against equity-based pay per se, but he does argue that too few companies properly link pay and performance (Principle 6). Buffett uses Geico, Berkshire’s auto insurance business, to illustrate the company’s compensation philosophy. The goals of the plan, Buffett explains, “should be (1) tailored to the economics of the specific operating business; (2) simple in character so that the degree to which they are being realized can be easily measured; and (3) directly related to the daily activities of plan participants.” He states that “we shun ‘lottery ticket’ arrangementswhose ultimate valueis totally out of the control of the person whose behavior we would like to affect” (Principles 7 and 8).

So far, Berkshire looks like a complete level 10 value-creation company—one that applies all ten principles. But it doesn’t closely adhere to Principle 4 (carry only assets that maximize value) and has never acted on Principle 5 (return cash to shareholders). In both cases, however, Buffett and Munger’s writings and comments suggest that Berkshire evaluates its investments in light of these principles even if it doesn’t directly apply them to itself. Principle 4 advises selling operations if a buyer offers a meaningful premium to estimated value. Buffett states flatly, “Regardless of price, we have no interest at all in selling any good businesses that Berkshire owns,” noting that this attitude “hurts our financial performance.” And despite sitting on more than $40 billion in excess cash at year-end 2005, Berkshire has not returned any cash to its shareholders to date. However, the company does apply a clear test to determine the virtue of retaining, versus distributing, cash: Management assesses “whether retention, over time, delivers shareholders at least $1 of market value for each $1 retained.” This test, of course, is a restatement of the core shareholder value concept that all investments should generate a return in excess of the cost of capital. Consistent with Principle 5, Buffett is clear about the consequence of failing this test.

He says, “If we reach the point that we can’t create extra value by retaining earnings, we will pay them out and let our shareholders deploy the funds.” Buffett’s influence extends beyond Berkshire to companies for which he has served as a board member. For example, the Washington Post and Coca-Cola were among the first companies to voluntarily expense employee stock options in 2002. Companies with which Buffett has been involved also have a history of repurchasing stock.

Sources for quotations include Berkshire Hathaway’s own publications and various public news outlets. Mauboussin is the chief investment strategist at Legg Mason Capital Management, based in Baltimore. He is a shareholder in Berkshire Hathaway. Principle 1 Do not manage earnings or provide earnings guidance. Companies that fail to embrace this first principle of shareholder value will almost certainly be unable to follow the rest. Unfortunately, that rules out most corporations because virtually all public companies play the earnings expectations game. A 2006 National Investor Relations Institute study found that 66% of 654 surveyed companies provide regular profit guidance to Wall Street analysts.

A 2005 survey of 401 financial executives by Duke University’s John Graham and Campbell R. Harvey, and University of Washington’s Shivaram Rajgopal, reveals that companies manage earnings with more than just accounting gimmicks: A startling 80% of respondents said they would decrease value-creating spending on research and development, advertising, maintenance, and hiring in order to meet earnings benchmarks.

More than half the executives would delay a new project even if it entailed sacrificing value. What’s so bad about focusing on earnings? First, the accountant’s bottom line approximates neither a company’s value nor its change in value over the reporting period. Second, organizations compromise value when they invest at rates below the cost of capital (overinvestment) or forgo investment in value-creating opportunities (underinvestment) in an attempt to boost short-term earnings. Third, the practice of reporting rosy earnings via value-destroying operating decisions or by stretching permissible accounting to the limit eventually catches up with companies. Those that can no longer meet investor expectations end up destroying a substantial portion, if not all, of their market value.

WorldCom, Enron, and Nortel Networks are notable examples. Principle 2 Make strategic decisions that maximize expected value, even at the expense of lowering near-term earnings. Companies that manage earnings are almost bound to break this second cardinal principle. Indeed, most companies evaluate and compare strategic decisions in terms of the estimated impact on reported earnings when they should be measuring against the expected incremental value of future cash flows instead. Expected value is the weighted average value for a range of plausible scenarios.

(To calculate it, multiply the value added for each scenario by the probability that that scenario will materialize, then sum up the results.) A sound strategic analysis by a company’s operating units should produce informed responses to three questions: First, how do alternative strategies affect value? Second, which strategy is most likely to create the greatest value? Third, for the selected strategy, how sensitive is the value of the most likely scenario to potential shifts in competitive dynamics and assumptions about technology life cycles, the regulatory environment, and other relevant variables? At the corporate level, executives must also address three questions: Do any of the operating units have sufficient value-creation potential to warrant additional capital? Which units have limited potential and therefore should be candidates for restructuring or divestiture? And what mix of investments in operating units is likely to produce the most overall value? Principle 3 Make acquisitions that maximize expected value, even at the expense of lowering near-term earnings.

Companies typically create most of their value through day-to-day operations, but a major acquisition can create or destroy value faster than any other corporate activity. With record levels of cash and relatively low debt levels, companies increasingly use mergers and acquisitions to improve their competitive positions: M&A announcements worldwide exceeded $2.7 trillion in 2005. Companies (even those that follow Principle 2 in other respects) and their investment bankers usually consider price/earnings multiples for comparable acquisitions and the immediate impact of earnings per share (EPS) to assess the attractiveness of a deal. They view EPS accretion as good news and its dilution as bad news. When it comes to exchange-of-shares mergers, a narrow focus on EPS poses an additional problem on top of the normal shortcomings of earnings. Whenever the acquiring company’s price/earnings multiple is greater than the selling company’s multiple, EPS rises.

The inverse is also true. If the acquiring company’s multiple is lower than the selling company’s multiple, earnings per share decline. In neither case does EPS tell us anything about the deal’s long-term potential to add value. Sound decisions about M&A deals are based on their prospects for creating value, not on their immediate EPS impact, and this is the foundation for the third principle of value creation.

Management needs to identify clearly where, when, and how it can accomplish real performance gains by estimating the present value of the resulting incremental cash flows and then subtracting the acquisition premium. Value-oriented managements and boards also carefully evaluate the risk that anticipated synergies may not materialize. They recognize the challenge of postmerger integration and the likelihood that competitors will not stand idly by while the acquiring company attempts to generate synergies at their expense. If it is financially feasible, acquiring companies confident of achieving synergies greater than the premium will pay cash so that their shareholders will not have to give up any anticipated merger gains to the selling companies’ shareholders. If management is uncertain whether the deal will generate synergies, it can hedge its bets by offering stock.

This reduces potential losses for the acquiring company’s shareholders by diluting their ownership interest in the postmerger company. Principle 4 Carry only assets that maximize value. The fourth principle takes value creation to a new level because it guides the choice of business model that value-conscious companies will adopt. There are two parts to this principle. First, value-oriented companies regularly monitor whether there are buyers willing to pay a meaningful premium over the estimated cash flow value to the company for its business units, brands, real estate, and other detachable assets. Such an analysis is clearly a political minefield for businesses that are performing relatively well against projections or competitors but are clearly more valuable in the hands of others.

London Metropolitan University

Yet failure to exploit such opportunities can seriously compromise shareholder value. A recent example is Kmart. ESL Investments, a hedge fund operated by Edward Lampert, gained control of Kmart for less than $1 billion when it was under bankruptcy protection in 2002 and when its shares were trading at less than $1. Lampert was able to recoup almost his entire investment by selling stores to Home Depot and Sears, Roebuck. In addition, he closed underperforming stores, focused on profitability by reducing capital spending and inventory levels, and eliminated Kmart’s traditional clearance sales. By the end of 2003, shares were trading at about $30; in the following year they surged to $100; and, in a deal announced in November 2004, they were used to acquire Sears. Former shareholders of Kmart are justifiably asking why the previous management was unable to similarly reinvigorate the company and why they had to liquidate their shares at distressed prices.

Second, companies can reduce the capital they employ and increase value in two ways: by focusing on high value-added activities (such as research, design, and marketing) where they enjoy a comparative advantage and by outsourcing low value-added activities (like manufacturing) when these activities can be reliably performed by others at lower cost. Examples that come to mind include Apple Computer, whose iPod is designed in Cupertino, California, and manufactured in Taiwan, and hotel companies such as Hilton Hospitality and Marriott International, which manage hotels without owning them.

And then there’s Dell’s well-chronicled direct-to-customer, custom PC assembly business model, which minimizes the capital the company needs to invest in a sales force and distribution, as well as the need to carry inventories and invest in manufacturing facilities. Principle 5 Return cash to shareholders when there are no credible value-creating opportunities to invest in the business. Even companies that base their strategic decision making on sound value-creation principles can slip up when it comes to decisions about cash distribution. The importance of adhering to the fifth principle has never been greater: As of the first quarter of 2006, industrial companies in the S&P 500 were sitting on more than $643 billion in cash—an amount that is likely to grow as companies continue to generate positive free cash flows at record levels.

Value-conscious companies with large amounts of excess cash and only limited value-creating investment opportunities return the money to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks. Not only does this give shareholders a chance to earn better returns elsewhere, but it also reduces the risk that management will use the excess cash to make value-destroying investments—in particular, ill-advised, overpriced acquisitions.

Just because a company engages in share buybacks, however, doesn’t mean that it abides by this principle. Many companies buy back shares purely to boost EPS, and, just as in the case of mergers and acquisitions, EPS accretion or dilution has nothing to do with whether or not a buyback makes economic sense.

When an immediate boost to EPS rather than value creation dictates share buyback decisions, the selling shareholders gain at the expense of the nontendering shareholders if overvalued shares are repurchased. Especially widespread are buyback programs that offset the EPS dilution from employee stock option programs. In those kinds of situations, employee option exercises, rather than valuation, determine the number of shares the company purchases and the prices it pays. Value-conscious companies repurchase shares only when the company’s stock is trading below management’s best estimate of value and no better return is available from investing in the business. Companies that follow this guideline serve the interests of the nontendering shareholders, who, if management’s valuation assessment is correct, gain at the expense of the tendering shareholders. When a company’s shares are expensive and there’s no good long-term value to be had from investing in the business, paying dividends is probably the best option.

Principle 6 Reward CEOs and other senior executives for delivering superior long-term returns. Companies need effective pay incentives at every level to maximize the potential for superior returns. Principles 6, 7, and 8 set out appropriate guidelines for top, middle, and lower management compensation. I’ll begin with senior executives. As I’ve already observed, stock options were once widely touted as evidence of a healthy value ethos. The standard option, however, is an imperfect vehicle for motivating long-term, value-maximizing behavior. First, standard stock options reward performance well below superior-return levels.

As became painfully evident in the 1990s, in a rising market, executives realize gains from any increase in share price—even one substantially below gains reaped by their competitors or the broad market. Second, the typical vesting period of three or four years, coupled with executives’ propensity to cash out early, significantly diminishes the long-term motivation that options are intended to provide. Finally, when options are hopelessly underwater, they lose their ability to motivate at all. And that happens more frequently than is generally believed. For example, about one-third of all options held by U. Executives were below strike prices in 1999 at the height of the bull market.

But the supposed remedies—increasing cash compensation, granting restricted stock or more options, or lowering the exercise price of existing options—are shareholder-unfriendly responses that rewrite the rules in midstream. Value-conscious companies can overcome the shortcomings of standard employee stock options by adopting either a discounted indexed-option plan or a discounted equity risk option (DERO) plan. Indexed options reward executives only if the company’s shares outperform the index of the company’s peers—not simply because the market is rising. To provide management with a continuing incentive to maximize value, companies can lower exercise prices for indexed options so that executives profit from performance levels modestly below the index. Companies can address the other shortcoming of standard options—holding periods that are too short—by extending vesting periods and requiring executives to hang on to a meaningful fraction of the equity stakes they obtain from exercising their options. For companies unable to develop a reasonable peer index, DEROs are a suitable alternative. The DERO exercise price rises annually by the yield to maturity on the ten-year U.S.

Treasury note plus a fraction of the expected equity risk premium minus dividends paid to the holders of the underlying shares. Equity investors expect a minimum return consisting of the risk-free rate plus the equity risk premium. But this threshold level of performance may cause many executives to hold underwater options. By incorporating only a fraction of the estimated equity risk premium into the exercise price growth rate, a board is betting that the value added by management will more than offset the costlier options granted. Dividends are deducted from the exercise price to remove the incentive for companies to hold back dividends when they have no value-creating investment opportunities. Principle 7 Reward operating-unit executives for adding superior multiyear value.

While properly structured stock options are useful for corporate executives, whose mandate is to raise the performance of the company as a whole—and thus, ultimately, the stock price—such options are usually inappropriate for rewarding operating-unit executives, who have a limited impact on overall performance. A stock price that declines because of disappointing performance in other parts of the company may unfairly penalize the executives of the operating units that are doing exceptionally well. Alternatively, if an operating unit does poorly but the company’s shares rise because of superior performance by other units, the executives of that unit will enjoy an unearned windfall. In neither case do option grants motivate executives to create long-term value. Only when a company’s operating units are truly interdependent can the share price serve as a fair and useful indicator of operating performance. Companies typically have both annual and long-term (most often three-year) incentive plans that reward operating executives for exceeding goals for financial metrics, such as revenue and operating income, and sometimes for beating nonfinancial targets as well. The trouble is that linking bonuses to the budgeting process induces managers to lowball performance possibilities.

More important, the usual earnings and other accounting metrics, particularly when used as quarterly and annual measures, are not reliably linked to the long-term cash flows that produce shareholder value. To create incentives for an operating unit, companies need to develop metrics such as shareholder value added (SVA).

To calculate SVA, apply standard discounting techniques to forecasted operating cash flows that are driven by sales growth and operating margins, then subtract the investments made during the period. Because SVA is based entirely on cash flows, it does not introduce accounting distortions, which gives it a clear advantage over traditional measures. To ensure that the metric captures long-term performance, companies should extend the performance evaluation period to at least, say, a rolling three-year cycle. The program can then retain a portion of the incentive payouts to cover possible future underperformance. This approach eliminates the need for two plans by combining the annual and long-term incentive plans into one.

Instead of setting budget-based thresholds for incentive compensation, companies can develop standards for superior year-to-year performance improvement, peer benchmarking, and even performance expectations implied by the share price. Principle 8 Reward middle managers and frontline employees for delivering superior performance on the key value drivers that they influence directly.

Although sales growth, operating margins, and capital expenditures are useful financial indicators for tracking operating-unit SVA, they are too broad to provide much day-to-day guidance for middle managers and frontline employees, who need to know what specific actions they should take to increase SVA. For more specific measures, companies can develop leading indicators of value, which are quantifiable, easily communicated current accomplishments that frontline employees can influence directly and that significantly affect the long-term value of the business in a positive way. Examples might include time to market for new product launches, employee turnover rate, customer retention rate, and the timely opening of new stores or manufacturing facilities.

My own experience suggests that most businesses can focus on three to five leading indicators and capture an important part of their long-term value-creation potential. The process of identifying leading indicators can be challenging, but improving leading-indicator performance is the foundation for achieving superior SVA, which in turn serves to increase long-term shareholder returns. Principle 9 Require senior executives to bear the risks of ownership just as shareholders do. For the most part, option grants have not successfully aligned the long-term interests of senior executives and shareholders because the former routinely cash out vested options. The ability to sell shares early may in fact motivate them to focus on near-term earnings results rather than on long-term value in order to boost the current stock price. To better align these interests, many companies have adopted stock ownership guidelines for senior management.

Minimum ownership is usually expressed as a multiple of base salary, which is then converted to a specified number of shares. For example, eBay’s guidelines require the CEO to own stock in the company equivalent to five times annual base salary. For other executives, the corresponding number is three times salary.

Top managers are further required to retain a percentage of shares resulting from the exercise of stock options until they amass the stipulated number of shares. But in most cases, stock ownership plans fail to expose executives to the same levels of risk that shareholders bear. One reason is that some companies forgive stock purchase loans when shares underperform, claiming that the arrangement no longer provides an incentive for top management. Such companies, just as those that reprice options, risk institutionalizing a pay delivery system that subverts the spirit and objectives of the incentive compensation program. Another reason is that outright grants of restricted stock, which are essentially options with an exercise price of $0, typically count as shares toward satisfaction of minimum ownership levels.

Stock grants motivate key executives to stay with the company until the restrictions lapse, typically within three or four years, and they can cash in their shares. These grants create a strong incentive for CEOs and other top managers to play it safe, protect existing value, and avoid getting fired. Not surprisingly, restricted stock plans are commonly referred to as “pay for pulse,” rather than pay for performance.

In an effort to deflect the criticism that restricted stock plans are a giveaway, many companies offer performance shares that require not only that the executive remain on the payroll but also that the company achieve predetermined performance goals tied to EPS growth, revenue targets, or return-on-capital-employed thresholds. While performance shares do demand performance, it’s generally not the right kind of performance for delivering long-term value because the metrics are usually not closely linked to value. Companies need to balance the benefits of requiring senior executives to hold continuing ownership stakes and the resulting restrictions on their liquidity and diversification.

Companies seeking to better align the interests of executives and shareholders need to find a proper balance between the benefits of requiring senior executives to have meaningful and continuing ownership stakes and the resulting restrictions on their liquidity and diversification. Without equity-based incentives, executives may become excessively risk averse to avoid failure and possible dismissal. If they own too much equity, however, they may also eschew risk to preserve the value of their largely undiversified portfolios. Extending the period before executives can unload shares from the exercise of options and not counting restricted stock grants as shares toward minimum ownership levels would certainly help equalize executives’ and shareholders’ risks.

Principle 10 Provide investors with value-relevant information. The final principle governs investor communications, such as a company’s financial reports. Better disclosure not only offers an antidote to short-term earnings obsession but also serves to lessen investor uncertainty and so potentially reduce the cost of capital and increase the share price. One way to do this, as described in my article “The Economics of Short-Term Performance Obsession” in the May–June 2005 issue of Financial Analysts Journal, is to prepare a corporate performance statement. Investors need a baseline for assessing a company’s cash flow prospects and a clear view of their potential volatility. The corporate performance statement provides a way to estimate both things by separating realized cash flows from forward-looking accruals. Operating cash flows.

The first part of this statement tracks only operating cash flows. It does not replace the traditional cash flow statement because it excludes cash flows from financing activities—new issues of stocks, stock buybacks, new borrowing, repayment of previous borrowing, and interest payments. Revenue and expense accruals. The second part of the statement presents revenue and expense accruals, which estimate future cash receipts and payments triggered by current sales and purchase transactions. Management estimates three scenarios—most likely, optimistic, and pessimistic—for accruals of varying levels of uncertainty characterized by long cash-conversion cycles and wide ranges of plausible outcomes. Management discussion and analysis. In the third section, management presents the company’s business model, key performance indicators (both financial and nonfinancial), and the critical assumptions supporting each accrual estimate.

Could such specific disclosure prove too costly? The reality is that executives in well-managed companies already use the type of information contained in a corporate performance statement. Indeed, the absence of such information should cause shareholders to question whether management has a comprehensive grasp of the business and whether the board is properly exercising its oversight responsibility. In the present unforgiving climate for accounting shenanigans, value-driven companies have an unprecedented opportunity to create value simply by improving the form and content of corporate reports.

The Rewards—and the Risks The crucial question, of course, is whether following these ten principles serves the long-term interests of shareholders. For most companies, the answer is a resounding yes. Just eliminating the practice of delaying or forgoing value-creating investments to meet quarterly earnings targets can make a significant difference. Further, exiting the earnings-management game of accelerating revenues into the current period and deferring expenses to future periods reduces the risk that, over time, a company will be unable to meet market expectations and trigger a meltdown in its stock. But the real payoff comes in the difference that a true shareholder-value orientation makes to a company’s long-term growth strategy.

For most organizations, value-creating growth is the strategic challenge, and to succeed, companies must be good at developing new, potentially disruptive businesses. The bulk of the typical company’s share price reflects expectations for the growth of current businesses. If companies meet those expectations, shareholders will earn only a normal return. But to deliver superior long-term returns—that is, to grow the share price faster than competitors’ share prices—management must either repeatedly exceed market expectations for its current businesses or develop new value-creating businesses. It’s almost impossible to repeatedly beat expectations for current businesses, because if you do, investors simply raise the bar. So the only reasonable way to deliver superior long-term returns is to focus on new business opportunities. (Of course, if a company’s stock price already reflects expectations with regard to new businesses—which it may do if management has a track record of delivering such value-creating growth—then the task of generating superior returns becomes daunting; it’s all managers can do to meet the expectations that exist.).

Value-creating growth is the strategic challenge, and to succeed, companies must be good at developing new, potentially disruptive businesses. Companies focused on short-term performance measures are doomed to fail in delivering on a value-creating growth strategy because they are forced to concentrate on existing businesses rather than on developing new ones for the longer term. When managers spend too much time on core businesses, they end up with no new opportunities in the pipeline. And when they get into trouble—as they inevitably do—they have little choice but to try to pull a rabbit out of the hat. The dynamic of this failure has been very accurately described by Clay Christensen and Michael Raynor in their book The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth (Harvard Business School Press, 2003).

With a little adaptation, it plays out like this:. Despite a slowdown in growth and margin erosion in the company’s maturing core business, management continues to focus on developing it at the expense of launching new growth businesses. Eventually, investments in the core can no longer produce the growth that investors expect, and the stock price takes a hit. To revitalize the stock price, management announces a targeted growth rate that is well beyond what the core can deliver, thus introducing a larger growth gap. Confronted with this gap, the company limits funding to projects that promise very large, very fast growth.

Accordingly, the company refuses to fund new growth businesses that could ultimately fuel the company’s expansion but couldn’t get big enough fast enough. Managers then respond with overly optimistic projections to gain funding for initiatives in large existing markets that are potentially capable of generating sufficient revenue quickly enough to satisfy investor expectations. To meet the planned timetable for rollout, the company puts a sizable cost structure in place before realizing any revenues.

As revenue increases fall short and losses persist, the market again hammers the stock price and a new CEO is brought in to shore it up. Seeing that the new growth business pipeline is virtually empty, the incoming CEO tries to quickly stem losses by approving only expenditures that bolster the mature core. The company has now come full circle and has lost substantial shareholder value. Companies that take shareholder value seriously avoid this self-reinforcing pattern of behavior. Because they do not dwell on the market’s near-term expectations, they don’t wait for the core to deteriorate before they invest in new growth opportunities. They are, therefore, more likely to become first movers in a market and erect formidable barriers to entry through scale or learning economies, positive network effects, or reputational advantages. Their management teams are forward-looking and sensitive to strategic opportunities.

Over time, they get better than their competitors at seizing opportunities to achieve competitive advantage. Although applying the ten principles will improve long-term prospects for many companies, a few will still experience problems if investors remain fixated on near-term earnings, because in certain situations a weak stock price can actually affect operating performance.

The risk is particularly acute for companies such as high-tech start-ups, which depend heavily on a healthy stock price to finance growth and send positive signals to employees, customers, and suppliers. When share prices are depressed, selling new shares either prohibitively dilutes current shareholders’ stakes or, in some cases, makes the company unattractive to prospective investors. As a consequence, management may have to defer or scrap its value-creating growth plans. Then, as investors become aware of the situation, the stock price continues to slide, possibly leading to a takeover at a fire-sale price or to bankruptcy. Severely capital-constrained companies can also be vulnerable, especially if labor markets are tight, customers are few, or suppliers are particularly powerful. A low share price means that these organizations cannot offer credible prospects of large stock-option or restricted-stock gains, which makes it difficult to attract and retain the talent whose knowledge, ideas, and skills have increasingly become a dominant source of value.

From the perspective of customers, a low valuation raises doubts about the company’s competitive and financial strength as well as its ability to continue producing high-quality, leading-edge products and reliable postsale support. Suppliers and distributors may also react by offering less favorable contractual terms, or, if they sense an unacceptable probability of financial distress, they may simply refuse to do business with the company.

In all cases, the company’s woes are compounded when lenders consider the performance risks arising from a weak stock price and demand higher interest rates and more restrictive loan terms. Clearly, if a company is vulnerable in these respects, then responsible managers cannot afford to ignore market pressures for short-term performance, and adoption of the ten principles needs to be somewhat tempered. But the reality is that these extreme conditions do not apply to most established, publicly traded companies. Few rely on equity issues to finance growth. Most generate enough cash to pay their top employees well without resorting to equity incentives. Most also have a large universe of customers and suppliers to deal with, and there are plenty of banks after their business. It’s time, therefore, for boards and CEOs to step up and seize the moment.

The sooner you make your firm a level 10 company, the more you and your shareholders stand to gain. And what better moment than now for institutional investors to act on behalf of the shareholders and beneficiaries they represent and insist that long-term shareholder value become the governing principle for all the companies in their portfolios?

Free PDF Creating Shareholder Value: A Guide for Managers and Investors Books Online. 1. Free PDF Creating Shareholder Value: A Guide for Managers and Investors Books Online. Book details Author: Alfred Rappaport Pages: 224 pages Publisher: Free Press 1997-12-01 Language: English ISBN-10: ISBN-13: 107. Description this book In this substantially revised and updated edition of his 1986 business classic, Creating Shareholder Value, Alfred Rappaport provides managers and investors with the practical tools needed to generate superior returns.The ultimate test of corporate strategy, the only reliable measure, is whether it creates economic value for shareholders. After a decade of downsizings frequently blamed on shareholder value decision making, this book presents a new and indepth assessment of the rationale for shareholder value.

Further, Rappaport presents provocative new insights on shareholder value applications to: (1) business planning, (2) performance evaluation, (3) executive compensation, (4) mergers and acquisitions, (5) interpreting stock market signals, and (6) organizational implementation. Readers will be particularly interested in Rappaport s answers to three management performance evaluation questions: (1) What is the most appropriate measure of performance? (2) What is the most appropriate target level of performance? And (3) How should rewards be linked to performance? The recent acquisition of Duracell International by Gillette is analyzed in detail, enabling the reader to understand the critical information needed when. assessing the risks and rewards of a merger from both sides of the negotiating table. The shareholder value approach presented here has been widely embraced by publicly traded as well as privately held companies worldwide.